When Fernando Santos stepped aside after eight years, Portugal’s federation faced a riddle as old as the game itself: how do you replace the man who delivered the nation’s first major trophy yet left supporters craving more fluent football? The answer arrived on 9 January 2023 in the form of Roberto Martínez, the Spaniard who had spent the previous six years coaxing flair from Belgium’s “golden generation” without ever unlocking silverware.

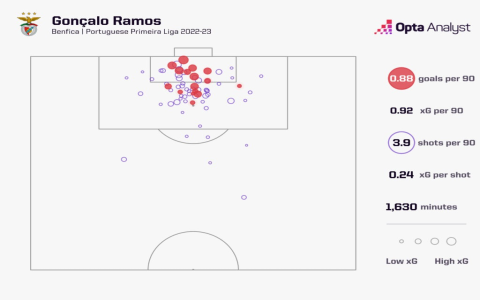

Martínez’s appointment shattered two taboos. First, he became the first foreign head coach to take permanent charge of A Seleção, ending 99 years of Portuguese-only rule. Second, he accepted a job many domestic legends—José Mourinho, Jorge Jesus, even Rui Vitória—politely dodged, wary of a squad at a generational crossroads. Cristiano Ronaldo’s 40th birthday looms, while João Félix, Rafael Leão and Gonçalo Ramos push for centre stage. Martínez, ever the diplomat, called it “a portfolio of talent any coach would mortgage his house for.”

From day one the Catalan has preached “controlled aggression,” a phrase designed to calm those who still wince at Belgium’s quarter-final exits. In his maiden press conference he produced a tablet filled with heat-maps of Bernardo Silva’s touches, arguing Portugal lost to Morocco in 2022 because they “won the ball in the wrong postcode.” He has since banned the word “transição,” insisting “we don’t transition, we invite.” The semantic tweak matters: training sessions now finish with 15-minute games of 8v8 in a 30-metre square, an drill borrowed from Pep Guardiola’s 2011 Barcelona manual that forces full-backs into midfield overloads.

The early returns are persuasive. Across the opening four Euro 2024 qualifiers Portugal scored 14 goals, nine from open play, with an average possession of 63 percent—seven points higher than Santos’s last competitive cycle. Yet questions persist. Can Martínez, a coach branded “too nice” by sections of the Belgian press, impose discipline on a squad split between Ronaldo loyalists and younger stars who grew up on FIFA, not Euro 2016? The answer may lie in his back-room architecture. He retained national icon Rui Costa as technical director, handed former captain Ricardo Carvalho the individual-defence brief, and lured performance guru Richard Evans from the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks to monitor heart-rate variability. The message: evolution, not revolution.

Off the pitch, Martínez has embraced Portuguese culture with the fervour of a fado convert. He rents a 19th-century townhouse in Lisbon’s Alfama district, orders galão at the same café every morning and quizzes locals on the difference between a cavaquinho and a bandolim. “Integration is tactics,” he told staff after hiring a language tutor who doubles as his yoga instructor. Players report Whatsapp voice notes delivered in accented but enthusiastic Portuguese; Ronaldo allegedly replied with 17 laughing emojis.

The spectre of Mourinho still circles. The Roma coach remains the people’s choice, fuelled by pundits who claim only a native son can handle the Lisbon—Porto club divide. But Martínez has weaponised that skepticism, screening clips of outsiders who thrived abroad: Lippi in Italy, Hiddink in Russia, even Southgate in England. The subtext: football passports are obsolete.

As Portugal prepares for a potential knockout meeting with France or England next summer, Martínez faces the same metric that haunted Belgium: can aesthetic ambition survive single-elimination chaos? He answers with a statistic of his own: in 46 competitive matches with Belgium his team conceded only four goals from set-pieces. “Beauty without bolts on the door is just perfume,” he remarked after a 3-0 win over Bosnia. Whether that pragmatism can carry Portugal past the quarter-final frontier may decide if the first foreign coach becomes the latest local hero—or merely a colourful footnote in the endless search for footballing identity.